Who shot Dhlulamithi?

Mystery surrounds the eventual fate of the mighty elephant that changed the life of the legendary poacher ‘Bvekenya’

In the late 1929, Stephanus Cecil Rutgert Barnard sighted his rifle on an elephant with tusks that stretched to the ground. This event was to mark a turning point for the famed elephant poacher, who is better remembered by his Shangaan nickname of Bvekenya. The encounter is dramatically recounted in TV Bulpin’s book The Ivory Trail. For years Barnard had dreamt of this moment, of shooting the elephant called Dhlulamithi (a Shangaan word meaning, ‘taller that the trees’), but Bvekenya couldn’t bring himself to pull the trigger and then and there decided to give up the way of the gun.

In years since Bvekenya left his favorite haunts around Crooks Corner, where the boundaries of South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique meet, the question has been asked: whatever happened to Dhlulamithi? Did he live out his days roaming the Gona-re-Zhou area in south eastern Zimbabwe where Bvekenya came across him or did he perhaps fall victim to another elephant poacher?

At first check it appears that Dhlulamithi did fall prey to a bullet, fired not by a poacher but rather a hunter. In August 1967 a South African Defense Force general, Victor Verster, shot a massive bull elephant in the Gona-re-Zhou nature reserve. Its tusks weighing 46 and 60kg were some of the largest to come out of the southern Africa. In the book he edited, neem uit die verlede, U de V. Pienaar claimed that this was Bvekenya’s elephant.

But Richard Harland, the professional hunter who guided Verster on the day he shot the elephant, is of a different opinion. “Firstly, Dhlulamithi is actually a hereditary title given to any big bull. And secondly, it was about 40 years after Bvekenya came across his elephant, so I think Bvekenya’s Dhlulamithi would have been long dead,” he says.

Elephant expert Anthony Hall Martin agrees with Harland. “When an elephant has tusks of that size, it’s probably in the last five years of its life,” he explains.

So to find out what happened to Bvekenya’s elephant we have to head further back into the past, where the likely suspects are somewhat obscured by history legend and bush rumor.

The most incredible story that is associated with Dhlulamithi is told by professional hunter and author Brian Marsh. While Marsh was operating in south eastern Zimbabwe in the 1960’s he and the game authorities used to come across dead elephants that had been show with a 4-bore muzzle loading rifle. According to Marsh, the story goes that the poacher was actually Bvekenya’s son by a Shangaan woman.

“He was a real will-o-the-wisp. The authorities could never catch him. He must have been a big man to handle a gun of that size.” Says Marsh. “It is said he even called himself Bvekenya and like his father, used to give meat to the local Shangaans who in return would hide hi and tell him when the authorities were in the area. It was also rumored that he shot Bvekenya’s Dhlulamithi.”

As to who this shadowy poacher actually was is a bit of a mystery, Bvekeny’s son. Izak, has no idea who this supposed half brother was and warns that it wouldn’t be the first time someone had impersonated his legendary father. “At least three people have pretended they were either my father or a family member,” says Izak.

Ron Thomson, author of the book The Adventures of Shadrek – Southern Africa’s Most Infamous Elephant Poacher, says “I only know of two poachers of any consequence who operated in south eastern Zimbabwe the first was Bvekenya and the second was Shadrek.” Shadrek’s life was just as colorful as that of Bvekenya, the son of a local Ndou chief, Shadrek poached elephant until he temporarily reformed his ways and worked with Thomson in the then Rhodesian game department.

Later the two of them were responsible for locating several ZANLA guerrilla camps in Mozambique during the Rhodesian bush War. “He was a short man and not a good shot, but he killed a lot of elephant.” Recalls Thomson.

However, Shadrek was too young to have shot Dhlulamithi. Nor, according to Thomson, did he ever hunt with a 4-bore muzzle loading rifle. “His weapon of choice was a 10.57 rifle and later an AK.47, ” says Thomson.

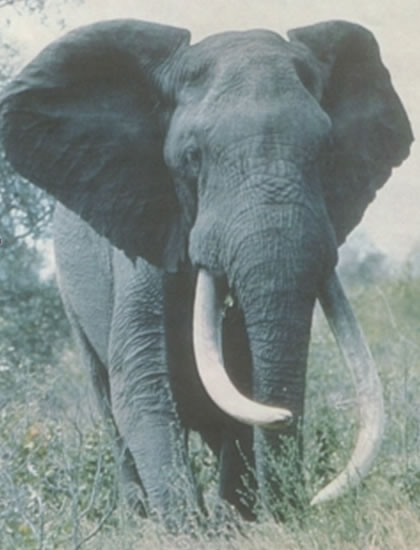

But perhaps the best clue as to what happened to the original Dhlulamithi lies in two black and white photographs. The first is believed to have been snapped by British South African (BSAP) policeman George Style, and appeared in the BSAP magazine. Outpost. The photograph shows a huge elephant who according to Izak, is the Dhlulamithi his father encountered.

During the 1920’s Style was stationed at Nuanetsi in Zimbabwe. Part of the area he had to police was Bvekenya’s old hunting ground. In an article he wrote for Outpost, he described how he eventually met up with the Bvekenya in South Africa and the two became friend, Style knew of the elephant that Bvekenya was obsessed with and took a photograph of it.

The second photograph appears in the book Conservationist and the Killers, by John Pringle, and shows a pair of huge tusks that are claimed to have come from Dhlulamithi. The caption says the tusks were sent to ivory trader R. Balmer in Lourenco Marques (Mat to) in 1932. He in turn exported them to England for auction by S Figgis and co. The tusks weighed a whopping 73 and 73.5kg.

“The two tusks are quite unusual and you can see by comparing the two photographs that they came from the same elephant,” says Izak.