Central Kalahari Safari

As a five year old barefoot boy, Izak Barnard loved to run to the post office, pushing the family wheelbarrow. The fact that the post office was 14 kilometers away didn't bother him much...

The Kalahari must be one of the most misunderstood biomes of Southern Africa. For centuries it’s been regarded as a place of mystery, an inhospitable wasteland where even today few dare to venture.

Although commonly referred to as a desert because of its porous sandy soils and almost total lack of surface water, most of the Kalahari is actually arid savanna with various depths of wind-blown sand held together by drought-resistant vegetation. The area actually receives more annual rainfall than the 200 millimeters or less defined for an extremely arid region: therefore, there is no such place as the Kalahari “Desert”.

From a geological perspective the 1.2 million square kilometer Kalahari Basin is one of the largest continuous areas of sand in the world and occupies much of Southern Africa. It’s a vast tract of life-sustaining plains that cover most of Botswana, stretching into South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe, and even as far north as Zambia, Angola and Zaire.

The closest you’ll get to true desert conditions is in the remote central Kalahari region which includes Central and Southwestern Botswana. Southeastern Namibia and the northern tip of the Northern Cape of South Africa.

In the Northern Cape the 960 000 hectare Kalahari Gemsbok National Park is well developed for tourism and you can safely visit the area in a hired car and overnight in its modern rest camps. Not so across the border in Botswana: the vast southern and central regions of this nation make up on of Africa’s last true wilderness area, an untamed wasteland where even the toughest adventures have succumbed to the harsh environment.

Pioneer explorer of the Central Kalahari is Izak Barnard, a well known character of the bush who first ventured into the heart of this great thirst land in the late 1950’s. He subsequently used his exploits and passion for the area to make a living by establishing Penduka Safaris, possibly the oldest safari company in Southern Africa. Even today Penduka is the only tour operator offering adventure trips into the very core of the Kalahari.

Izak was raised in a household oozing adventure. His father was the legendary ivory hunter Cecil Barnard, perhaps better known as Bvekenya, who based himself at Crooks Corner (now northernmost tip of the Kruger National Park) in the early 1900’s and successfully defied the law of three countries. His fascinating story is evocatively related in TV Bulpin’s book The Ivory Trail.

After many adventurous years in the bush, Bvekenya settled on the farm Vlakplaas in the Western Transvaal and married Maria Badenhorst who bore him four sons and a daughter. Also from tough descent, Maria was raised in one of those pioneering families which, in the 1880’s established the first trading store at Serowe in Eastern Botswana, as well as the first small hotel at Lake Ngami on the Southern fringes of the Okavango delta.

“During my childhood I listened to their stories of how woman and children crossed Kalahari and nearly died of thirst,” explained Izak with gravelly Afrikaans accent as he slipped through the gears of the huge International 4×4 (These women were part of the Dorland Trekkers, a loose gathering of die-hard Boers who in the late 1800’s trekked from the Transvaal to Angola in search of a new ‘promised land’).

“So it became my ideal to find out what was behind the next sand dune,” he

explained with a far-away look twinkling in his clear blue eyes.

Now, three decades after Izak’s exploratory trips, I was seated in one of his custom made safari vehicles – one of a lucky group of passengers on a 16 day Penduka safari into the heart of the Central Kalahari. I was greatly looking forward to experiencing this area with the wise old man of the Kalahari.

In the early days Izak was young man with no money, no experience, a two wheel drive that was of little use in the Kalahari deep sands, but with a heart that yearned for adventure.

He employed the help of the local Bakgalagadi tribesmen (a minority group of Botswana) and first experienced the Kalahari on foot with water and supplies being carried by donkey.

That’s how he met Simon Kooper, the son of a distinguished Nama leader (of the same name) who had battled with the Germans of South West Africa during the 1904 Nama rebellion. Simon became the friend and mentor who took him deep into the Kalahari, where he met clans of Bushmen and taught him to understand and respect the mysterious ways of this harsh area.

Now a seasoned 62 year old, Izak still leads trips through the Kalahari although his son Willem is gradually taking over the reins.

Izak’s dry, witty sense of humor goes with him, as he displayed after we had established our temporary home and settle round the camp fire on the first night: “At least I enjoy myself when the tourists fight with me because it makes me feel more at home,” he said with a smirk. Then he fired a question at one of the doctors on the trip: “Didn’t you know I’m related to Chris Barnard, the heart surgeon – can’t you see by the shape of my brain?” (They’re actually cousins).

Our journey started with a swift, uneventful passage from Izak’s farm in Delareyville in the Western Transvaal through the Makopong border post into Southern Botswana. That evening his team discussed our route and familiarized the guests with schedules and day-to-day safari activities.

Our larger than normal group consisted mainly of South African, with representation from Australia, Reunion, Scotland and Switzerland. (Normally a group numbers no more than 16 guests).

The punishing journey would include four highlights of the Central Kalahari region: Mabuasehaube Game Reserve in Southern Botswana, Masethleng Pan near the Namibian border and Khutse Game Reserve and the adjoining Central Kalahari Game which straddle the epicenter of Botswana like an elusive bull’s eye.

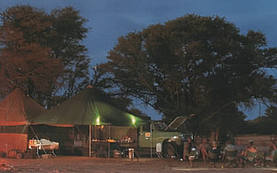

From the first evening I marveled at how quickly Izak’s team set up camp, and how each morning everything vanished into the vehicles with impressive efficiency.

A typical day would start with a wake-up call at sunrise (05h30), breakfast at 06h00, followed by a guided walk with Izak while his staff broke camp. If we were based in a particular area for a couple of days we would then head out for an early morning game drive. By 08h00 we were in the vehicles and ready for a full day’s travel. Apart from a scheduled one-hour lunch break the vehicles stopped only for specific highlights, such as visits to Bushmen villages, identification of the Kalahari’s fascinating plants and walks across vast clay pans. There were also those compulsory stops for petrol, water, drinks, extra supplies and settling park entry fees.

By 17h00 Izak and Willem would search for a suitable campsite and two hours later we would be seated round the fire sipping drinks and listening to one of Izak’s fascinating stories. Dinner was devoured with relish and by 20h00 the camp was enveloped by the sounds of soft snoring. “Everything depends on water,” explained Izak. (He has a really throaty way of pronouncing the word denoting the liquid of life: it’s a drawn out “wooorrterrr”).

Izak believes his guests should rough it a bit and Penduka is not the type of operation that deposits chocolates on your pillow each evening. Nevertheless, Izak insists on employing guides with a professional attitude who are prepared to work hard. His staff sees to everything from the loading and unloading of vehicles to the setting up of tents, stretchers and showers. Guests are encouraged to join in – and most do – but it’s not obligatory.

“We can carry only 4000 litres and our supply comes from boreholes. If they’re low we’ll have to save water for cooking and drinking as well as for the vehicles so you might have to endure a few days without a shower.”

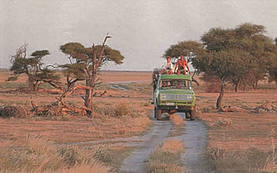

After many years of tackling the uncharted roads and tracks of the Kalahari with a variety of off road vehicles, Izak decided there was no vehicle on the market suitable for taking tourists into such remote regions. So he built his own. Our convoy consisted of four 4×4’s, three specially designed Internationals and a Toyota Land Cruiser.

Taking up the lead was a double cab International (referred to as ‘the double-cab’), which seated nine comfortably and took a hefty cargo in the load box. Next in line was a bus like station wagon International (known as die bus) with seating for 15. Following this was a supply vehicle (appropriately nicknamed die broodwa which describes its design), and taking up the rear was a heavily laden Land Cruiser (called ‘the cruiser’).

“Low revs are the secret of getting through the Kalahari’s hick sand,” revealed Izak, “so my V8, five litre engines produce 80 percent of their torque at 800 revs per minute. One of the vehicles, which was once a beaten up furniture removal truck, has 1, 1 million miles on the clock and in 20 years I’ve never broken a chassis or had to replace a gearbox.”

He must have had marathon sessions in the workshop because some vehicles were built from scratch and he tackled such complicated tasks as modifying chassis, rebuilding prop shafts and designing comfortable interiors. And the workshop goes with him because Izak’s dedicated team is geared to tackle almost any repair job in the bush.

Willem has obviously benefited from both a mechanical and an outdoor upbringing: you’ll find him sweating under a vehicle in the heat of the day, greased to the elbows, replacing a broken spring, and that evening he’ll be hunched over the campfire preparing a tasty cottage pie.

Abushehube is a 1972 square kilometer game reserve adjoining the 9 000 square kilometer Gemsbok National Park (which shares a common boundary with the Kalahari Gemsbok Nation Park in South Africa). Its landscape is dominated by hardy shrub vegetation interspersed with broad clay pans (shaped over the years by wind action), which are a vital part of the Kalahari ecosystem.

Large herbivores graze the sparse cover of grasses, dig for minerals and drink the mineralized water which remains in the pans for months after the summer rains. This in turn attracts large predators such as leopard, lion and spotted brown hyena.

These pans have also played a significant role in the human encroachment of the area, since they conveniently provided early settlers with water and grazing for their cattle. It was in recognition of this habitat destruction that Mabuasehube was established.

It took a solid day of driving on sandy, corrugated track to cover the 120 kilometres from our campsite near the border to this remote corner of Botswana.

Izak’s unusual knowledge of the Bushmen and his special relationship with them are also well known among researchers.

Izak, however, shuns fame and celebrity. He will rather tell you about the time when he and Simon Kooper found their way through the Kalahari with the help of only the sun, shade and the sand dunes.

That happened in the early 1960’s when Izak wanted to find the old ox wagon trail from Hukuntsi to the Gemsbok Park. People told him that it didn’t exist anymore, but Izak spoke to Simon Kooper, the leader of the Nama Hottentot people in Botswana. Simon told him: “I know the way. We used it when we walk to “Duits-Wes Afrika’.”

When we reached the rudimentary camp at Mpaathutlwa Pan (there’s no more than a long drop toilet) I could sense that Izak was disappointed.

“There’s been no rain,” he mused, string blankly at the bleak pan.

“That means there’s nothing to attract game and the herds will be migrating in search of other surface water and grazing.”

Our trip had been specifically arranged from March to coincide with the lush of green immediately after the summer rains, which is supposed to be the best time for game viewing here. Judging by the meager tufts of growth we encountered around the pan, Izak estimated that only a few millimeters had fallen since the previous rainy season.

Our game viewing was disappointing, the highlight being a brief sighting of four skittish lions that vanished in to a thick line of camelthorns Acacia erioloba and bastard umbrella thorns a. luederitzii lining the pan’s dune system (the wind action leaves a characteristic line of dunes, some as high as 30 metres, usually on the southern side). Other interesting sightings were distant views of herds of up to 30 springbok and brown hyena crossing the pan at night.

Izak was hoping for better luck further west near the Namibian border, so we pushed on north to Hukamtsi and linked with the sandy track to Masethleng Pan. For me, negotiating such torturous terrain was a valuable lesson in the reality of hard driving into remote areas – it took us two days to cover the 210 kilometres to Masethleng Pan.

Izak’s years of experience and determination showed, because he was always concerned about the performance of his vehicles. But then he’s learnt about them braking down in the bush the hard way.

In on ordeal he and Simon Kooper were crossing an extremely remote area of dune in a diesel Jeep. They switched off on a high crest to take compass bearings and discovered that the starter motor had come apart, leaving a trail of pieces in the sand.

Because Simon was nursing an injured foot (caused by a drum of diesel falling on it), Izak decided to back-track, thinking he would find all the parts within a few hundred meters.

He ended up walking 30 kilometres with no food and very little water. And to make matters worse on his return he discovered lion tracks on top of his own!

Then darkness descended and he spent that night shivering round a fire listening to the lions roaring. He made it back to the vehicle and re-assembled the starter motor, shaken and nervous, but a much wiser explorer.

On another occasion when he was driving alone the 4×4 linkage of his vehicle failed. He was lying underneath the vehicle repairing the problem when he felt something tugging at his let. It turned out to be a paw! And that paw belonged to a young lion trying to pull him from under the vehicle. He spent the night under his 4×4, dressed only in a pair of shorts in the middle of winter, hitting the lion’s paw with a spanner each time it appeared. A passing farmer eventually rescued him the following morning.

Yet more disappointment awaited us in the west – Masethleng Pan appeared as a hardened crust of clay and the surrounding dunes and plains were totally devoid of fresh growth.

In between the swirling dust devils and a vicious heat haze we could make out small groups of ostriches and herd of up to 50 springbok plodding across the pan in single file.

We spent two nights camped in a hauntingly beautiful acacia woodland 10 kilometres west of the pan. Here the gaunt plains were swathed in extensive groves of gnarled camelthorns, many of which had been shattered by lightning and appeared as charred limbs clawing at the cloudless skies.

Izak said the summer rains usually transform this area into a parkland of closely cropped green grass being grazed by herds of wildebeest, red hartebeest, springbok and gemsbok. “In 33 years of visiting the Kalahari I have never seen this area so dry,” he mused as we left for a walk early one morning. “But there’s more to the bush than big animals,” he added and set about identifying various plants and interpreting the maze of weird-looking tracks crisscrossing the caramel coloured sand.

“This is a female horned adder,” he reported, pointing with his walking stick to a snaking line in the sand. “How can you tell?” enquired on of the women in our group.

“Can’t you see the tracks of her high heeled shoes?” came his reply, the wit of which was revealed on close inspection: the female has much thinner tail than does the male, which leaves a line in the middle of its spoor.

Then he knelt next to a coin shaped incision in the sand and touched the lines of tightly grouped tracks leading to and from the hole.

“This is where a scorpion was cleaning out his home last night,” he explained, touching specks of discarded grass amid the tracks.

Izak produced a spade and set about digging out the quarry under scrutiny. It turned out to be quite a strenuous affair because the hole leading to its chamber descended at least a metre into the sand, twisting like a stairwell.

About 15 minutes later the 10 centimeter long, bright yellow buthidae scorpion appeared waving its pincers and arching its tail.

“Hold it there Izak,” one of the guests descended on him with an expensive Nikon.

Izak stared at her soberly, “I only go down on my knees in front of my wife, or bank manager.” The group had a good chuckle.

I was fascinated at the logical thought Izak employed when interpreting complicated signs. Tracking has always intrigued me and within half an hour he had pointed out the distinguishing characteristics of perplexing tracks of animals such as scrub hare, porcupine, bat eared fox, honey badger, and aardvark.

Another highlight of this part of the journey was a night drive to Masethleng Pan where we saw bat eared fox, Cape fox and aardvark. Round the camp fire Izak spoke for hours about his early experiences with game: in the mid 1960’s he and Simon Kooper used to count up to 42 000 head in a single drive from Tshane Pan near Hukuntsi to Masethleg Pan.

We hadn’t seen more than 200 animals, which indicated the rapid decline of wildlife since then. Said Izak, “As Masethleng we saw herds of 6 000 springbok and groups of up to 1 200 eland crossing the pan … and we used to dig holes in the clay and watch a Hillbrow of wild animals coming in to dig for phosphates. Sometimes we even watched lions bringing down hartebeest or gemsbok only 15 metres from where we were hiding.”

For the next leg of our journey we retraced the route to Hukuntsi where we stopped for petrol and supplies before setting off on the two day drive to Khutse Game Reserve, via the towns of Kang, Dutlwe, Lethakeng and Kungwane.

These remote settlements display bizarre contrasts of culture and it’s not unusual to encounter a modern telecommunications tower rising incongruously above an accumulation of tradition mud huts. Seemingly insignificant, these settlements are integral too much of the history of the Central Kalahari.

Hukuntsi is one of four villages clustered round Tshane Pan and was a bustling trading center during the days of early exploration. By today’s standards it is extremely remote but we found its stores so well stocked (especially Hukuntsi wholesalers) we could purchase anything from nail clippers to petrol.

Another interesting town is Lokwabe, home of the descendants of Simon Kooper.

In 1904, with the backing of 800 camels, the Germans pursued the Nama into Western Botswana where they engaged in a final showdown. After several trips to the area Izak has found camelthorn poles which supported the German’s heliograph, as well as a trail of ammunition belts, buckles, horseshoes and tin cans still inscribed with ‘Rindfleichund Bohnen Berlin 1904’

He’s still following what he calls the ‘Bully Beef Trail’ in the hope of finding this lost battlefield so it can be rightfully recorded.

After two more uneventful days of hard driving we entered the 2 590 square kilometer Khutse Game Reserve, the southern appendage of adjoining 51 800 square kilometer Central Kalahari game Reserve.

In these central regions of Botswana the landscape consists of vast plains mantled with golden grass and dotted with groves of drought-resistant trees such as the camelthorn, Kalahari apple leaf Lonchocarpus nelsii, silver cluster leaf Terminalia sericea, worm tree Albizia anthelmintica and mopane Colophospermum mopane. In an area devoid of surface water, the game has adapted to the harsh conditions by feeding on the water filled tsamma melon Citrullus ecirrhosus and gemsbok cucumber Acanthosicyos naudinianus and licking the dew from plants.

Khutse was also established to conserve the important pan ecosystem of the central Kalahari. Here the bush savanna is dotted with about 60 clay pans and interspersed with undulating and filled valleys, which are the remnants of an ancient drainage system that thousands of years ago flowed northwards into what is not the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

More bad news greeted us at the gate – the rangers reported little rain and a scarcity of game. There had, however, been sightings of large herds of springbok much further north in Deception Valley, the most famous game viewing area of the mammoth Central Kalahari Game Reserve. Izak therefore decided to cancel our stop at Khutse’s Moreswe Pan and add this time to our two-night stop at a Bushman Village at Molape and three night stop at Deception Valley.

It turned out to be a wise move because our game viewing at Khutse Pan amounted only to scattered herds of springbok and lonesome gemsbok braving the shimmering heat haze. A noteworthy sighting was a herd of 10 giraffe coming to slake their thirst from the pan’s borehole charged water hole.

The boreholes were yet another fascinating feature of the area. The central Kalahari might appear a maze of sandy, thinly grassed plains, but it actually has an abundance of underground water.

In recent years diamond prospecting geologists have mapped an extensive subterranean aquifer system, and the subsequent sinking of boreholes has brought great convenience to the area. Now farmers have enough water for their cattle, poplar water holes at game reserve have permanent supply (when the pump is in working order) and the semi nomadic Bushmen have less distance to travel in search of replenishment. 9Which, w were to learn, is the center of heated controversy).

Once again the testing terrain took its toll – it took two days of exhausting driving to cover the 190 kilometres between Khutse and Molape. We stopped every hour to clear grass seeds from the radiators and make sure no grass was collecting under the exhaust system. A blocked radiator results in an overheated engine, that can easily seize, and a hot exhaust can easily ignite trapped grass …

as well as your precious 4×4.

Although we had already enjoyed brief encounters with Bushmen clans at Metsamanong (en route to Molape) and at Ngwaatle Pan (just west of Hukuntsi), at Molape we had the rare opportunity to spend two fascinating days learning about their survival techniques and mysterious culture.

Izak was welcomed into the village like royalty. Within minutes of arriving throngs of meagerly clad Bushmen jostled round his vehicle. Men grinned warmly through wrinkled faces, women jabbered strings of excited sounding clicks, young children stared in awe and the agitated barking of scrawny dogs was rapidly reduced to howls as they skulked off after being pelted with an assortment of sticks, stones and bones. (One thing I rapidly learned about the Bushmen: if there is such a thing as reincarnation, don’t come back as one of their dogs!)

While Izak was being mobbed (some women even kissed his hands) Willem pointed out that his father had known this group of Ganakwe bushmen for decades and if we studied them carefully we might recognise few faces from the Spoornet television commercial. In 1992 Willem had selected about 30 of this clan and transported them to Makgadikgadi Pans for filming, after which they were handsomely rewarded with supplies and useful utensils.

Most of the foreign visitors were disappointed because the Bushmen we saw were not ‘wild’ and dressed in skins.

Indeed, many of them were clothed in a mixture of Western and ethnic garb. Seeing men wearing jeans, women adorned with plastic jewelry and toddler sporting a T shirt reading, “If you think I’m cute you should see my daddy’, is a far cry from anyone’s expectations of a tripe so famous for its instinctive knowledge of bush survival.

This triggered off a great deal of debate round the campfire so Izak revealed the sad tale of the demise of the true Bushmen.

“When I first went into the Kalahari the Bushmen clans we encountered used to run away from our vehicles.

“But as I got to know them better I was allowed to join them on their hunting expeditions and they would teach me all their tricks of the bush, like identifying spoor, how to set traps, which plants to eat, where to find water and how to prepare poison arrow.

“That’s when I realized they are actually sophisticated people and scientists in their own way because they have been successfully surviving in the Kalahari for thousands of years without doing any damage to the environment.”

Izak pointed out that most people have a totally false perception of the appearance and customs of the Bushmen.

“Everyone seems to think they are little men who sneak round the bush with poisoned arrows. But there are many different clans of Bushmen throughout the Kalahari some are six foot tall and specialize in hunting gemsbok with dogs and spears.

“This is actually how most of the gemsbok are killed in the Kalahari: the mongrels chase and bark at the gemsbok, which turns to fight instead of running away. The dogs distract the animal so much that one bushman managers to grab it by the horns while another stabs it in the neck.

This technique is much quicker and more effective than using poison arrows, when sometimes they have to track the animal for days waiting for the poison to take effect.”

Over the years Izak has worked on bushman projects with a host of writers, photographers and film makers (such as Sir Lourens Van Der Post, Anthony Banister, Frans Lanting of National Geographic fame, and the BB) and has subsequently become a walking, talking authority on the Kalahari Bushmen.

Sadly, he believes that today there are no more pure Bushmen and only a few extremely remote settlements, such as Molape, follow a semi traditional lifestyle.

Why are there no longer any pure Bushmen? “Because of interbreeding with other races as more and more people are encroaching on the Kalahari,” says Izak, “and then there’re the controversial boreholes.”

These are the center of the vicious circle of development aid. In line with modern development, the Botswana Government has embarked on a project to upgrade the Central Kalahari y providing the people with borehole water, as well as building houses, clinics, schools stores and suchlike.

Because there is nothing more important to the Bushmen than a supply of clean water, they settle round the boreholes. Within months the supply of natural food becomes exhausted and the government is forced to supply them with food. So their hunter gatherer lifestyle declines and the result is a squatter type camp of Bushmen who know only how to live off the Kalahari. And when the bottle stores arrive many succumb to alcohol abuse.

But it’s not entirely the government’s fault because Botswana is being pressurized by aid donors to look after it ‘undeveloped and impoverished’ people.

Perhaps much more thought and assessment should be directed at aid programmes before they are implemented or approved by sophisticated Europeans who have limited knowledge of a specific aria’s socioeconomic problems. Despite this controversy the people of Molape haven’t lost their bush skills and we were treated to an outing with six Bushmen in traditional attire who spent the day showing us how to live off the bush.

The leader, whose name I could best interpret as Rrdinojane, presented a formidable appearance. Barefoot and barrel chested, he strolled effortlessly through the bush digging up tubers and bulbs and chatting to Izak in a flurry of complex clicks.

The tiny yellow flower of an insignificant looking creeper was the tell tale sign of a massive underground tuber or wild cucumber Coccinia rhemanniana which is shaved and crushed by hand for its reserves of water. The root of the sand commiphor commiphora angolensis is chewed for its high moisture content, and the roots of the poison grub commiphora C. africana are the home of a species of Diamhidia beetle, which contains a concoction of haematoxic and neurotocix poisons used on the Bushmen’s deadly arrow.

We also watched the tribesmen crating fire by that classic method of rubbing pieces of wood together and making rope form mother in law’s tongue Sanservaria Scrabrifolia.

The common raisin bush Grewia Flava is an all purpose plant: it’s edible fruits are highly nutritious, the springy branches are made into arrows, strips of bark become weaving material for baskets and the roots are transformed into long tubes used as sucking sticks.

The branches of the silver cluster leaf Terminalia sericea are shaped into digging sticks and the bark is used for the tanning of skins. The leaves of the lavender tree Croton gratis-simus even provide the women with a supply of perfume.

Within a day this 'inhospitable wasteland' had been transformed before our eyes into a place where people could live and prosper.

The last leg of our trip took us 100 kilometers north to Deception valley, once part of an ancient drainage system but now a shallow depression within a magnificent expanse of rolling savanna scattered with contorted camelthorns.

Its name originates from the heat mirages which deceive your vision and play havoc with the imagination. This is where black backed jackals transform into black manned lions, a twisted stump merges into a prowling leopard and a marching secretary bird becomes an alert cheetah. It makes for frustrating game viewing if you don’t have binoculars.

The valley is famous for its game and the area was first brought to the notice of the public by controversial American couple Mark and Delia Owens. They based themselves at Deception Pan for eight years in order to conduct wildlife research and subsequently published the book Cry for the Kalahari, which hammered the Botswana government for the gross mismanagement of it wildlife area.

The couple was banned from the country and moved their efforts to Zambia’s Luangwa Valley, (rumor has it that they’ve recently been pardoned and granted permission to reenter Botswana.) We based ourselves at a rudimentary camping area that has recently been set aside on the western side of the valley and delved into three days of intense game viewing.

Fortunately our luck improved on drives sought to Piper Pans we encountered herds of up to 1 200 springbok decorating the horizon in a mingling mass of white and brown. Izak and I decided to concentrate this area hoping to encounter lurking predators, but on our return to camp we heard that the other vehicle to go out seen cheetah further north.

For our next drive we scoured this area without success and returned to base feeling dejected and discovered to our dismay that the other had seen two wild dogs!

During the final stretch back to Maun and its airport, which would reconnect me to reality, I thought long and hard about our 16 days in the bush, battling to identify that mysterious lure hat attracts visitors to the Kalahari. Even without game the vast tracts of flowing grass, cracked pans and weather beaten camelthorns reflect sow ell the peace and tranquility of the Central Kalahari.

For some people these all but desolate plains and seas of sand would illicit a profound agro phobia; for others, such as Izak Barnard, they are the very essence of adventure and spirit lifting freedom.